In a stage adaptation of the lauded novel, 'Kompoun' becomes a ritual of liberation

Family secrets, handed-down traumas, a search for truth, and storytelling as a ritual of healing: the play examines life’s darkest crevices, and in the process manages to engage, entertain and move.

One problem with theatre-in-the-round: if the on-stage action doesn’t quite grip you, there’s a likelihood that, as your focus starts to wander, you’ll end up watching audience members on the other side of the performance space. Sometimes you catch people on that side staring back; it can be quite embarrassing, and easy to get caught out because the poor actors in the middle will likely be aware that they’ve lost you.

There’s very little chance of being distracted by anything while watching Kompoun, a gripping new show that premiered early in May during Suidoosterfees, Cape Town’s annual Afrikaans arts festival. The show was performed in a no-frills rehearsal room, pretty much an austere black box somewhere in the back buildings at Artscape.

It’s a great venue for a show like this, since something of the makeshift environment filters into the performance, along with a great sense that what matters is not having a cosy, comfortable theatre to perform in, but the nuts and bolts of the storytelling. Kompoun, deftly directed by Lee-Ann van Rooi, is hard-hitting, rough, raw and gritty in the best sense of the word.

And it’s emotionally shattering. I only hope my tears didn’t distract people on the other side of the stage. There were quite a few.

It is a weighty show, adapted for the stage from Ronelda Kamfer’s novel which is something of a literary powerhouse, relentless and cutting. It examines various forms of trauma – family, childhood, generational – in an explicitly and distinctly South African context, conveyed through the observations, experiences and memories of cousins Nadia and Xavier (Xavie) McKinney. The show, despite the awfulness of some of the stories told, is gorgeously entertaining, very funny in places, and it’s fuelled by a wonderful sense of aliveness that’s generated by the two young actors, both bright-eyed and both gorgeous, who held me in their grip from start to finish.

These cousins arrive on stage in calf-length jeans and white Converses, along with plenty of attitude and Gloria Estefan’s “Conga Beat” playing like it’s the theme tune for their dance into battle . They’re on a mission to perform for us, and in so doing enact some kind of much-needed ritual of storytelling. They’re pretty hectic, too, and quite unapologetic.

They’re demanding of our attention, and they prove themselves wholly worthy of it.

Part of the play’s appeal is the language. It’s written in Kaaps (or Afrikaaps), which feels so close to the bone, possesses a kind of inherent poetry and musicality, and is incredibly visual. It is also rough. There’s are lines like, “Net ’n lekker man kry ’n poes op ’n silwer skinkbord!” (only a good man gets pussy on a silver tray), which effectively sums up both the ribald humour and the honest, if callous, kinds of observations that these two young characters are capable of sharing.

Kamfer has said that she gave the novel young narrators because youth is generally that time in our lives before we begin to compromise, before life’s focus turns to selfish risk-avoidance. In other words, we can rely on Nadia and Xavie to be honest and open with us; they have seen a lot and know a lot, but have not shut down the possibility of change, of escape, of hope.

And they are resilient, determined to claim the freedom they crave.

Nadia, who is played by the wonderful Melissa de Vries, at one point states that the play is “an intervention”, a way of breaking the cycle. She and Xavie, played by another lovely actor, Angelo Bergh, are the grandchildren of the stammoeder (clan mother, matriarch, ancestress) Sylvia McKinney, whose power over ensuing generations has a kind of hyperbolic, almost inescapable quality, as though there is a genetic cause for trauma, that it’s something inherited by birth.

But Nadia and Xavie represent a generation that is fed up and well aware that there’s nothing magical or inherited about what the people in their family have had to endure. To break the curse, they have to confront the past, recognise and address its mistakes, and refuse to be part of it.

It’s not magic or spell-casting they’re busy with, though, but storytelling, something ancient that humans have done since we first gathered around fires to collectively share our experiences.

They are on stage to talk about their family’s history and let slip its secrets, reveal their grandmother’s lies. Letting truths out of the bag is a kind of ritual of liberation, a gear shift, an upending of the status quo in order to break free from the stranglehold of abuse and end a cycle of handed-down trauma. By telling these stories, Xavie and Nadia are determined to stop the “generational curses” that have afflicted the McKinney clan.

And thus the play is a type of therapy, too – by sharing the burden of the past with the audience, Xavie and Nadia can perhaps empower us all to move forward, potentially unburdened. It is theatre as a kind of cleansing, breaking free, healing, and renewal.

It is sometimes very dark, often very bleak. And yet the play’s magic is that, rather than pulling the audience down, it manages to stay entertaining. A considerable achievement is how Van Rooi and her team have managed to inject lightness and upbeat energy into what could easily have been an entirely sombre affair. Sure, it is devastating from start to finish, full of heinous, horrific, no-holds-barred accounts of trauma and its myriad manifestations, but you feel the two actors holding your hand (sometimes tightly, sometimes with a hint of anger or despair) and guiding you through it. They somehow filter those harrowing, chilling experiences through a lens that makes them bearable without lessening their impact.

The play has an intensionally rough-and-ready look and feel, so much so that there’s an aura of improvisation to it, as if Xavie and Nadia are driven by rising impulses, or triggered to remember specific moments by the props and paraphernalia they find on the stage with them. What we get is a non-chronological account of everything from psychological torture and alcoholism, to bitterly dysfunctional relationships and violence against women and children.

It’s quite something, because so much of what the audience hears conveys something of the emotional claustrophobia of being trapped in an environment – in a community, in a family – where escape from the suffering seems impossible. This play makes you feel what it must be like to be stuck in that cycle of abuse, to have distress feel so much a part of your human experience that it’s hard to imagine any other way of being. And thus the cycle is perpetuated.

Among the cast of characters Xavie and Nadia bring to life, there are sociopaths like Auntie Daphne, and there is Diana, who is described as “a party animal for all eternity”, and there’s a mother who has developed arthritis, “because she’s a weak-ass fuck”. Not particularly pretty pictures, but this play is not here to beat around the bush. There are women abused by men and children abused by just about everyone, and there are victims forced to apologise when they’re the ones wronged or harmed or beaten.

And, along with the toxic family members they dredge up, there are also a few they decide they’d prefer not to enact because they’re, frankly, too far gone to resurrect, whose ghosts must rather be left alone.

Those characters that are brought to life are enacted using all manner of disguises, sometimes with parody, mockery and hilarious caricatures, sometimes with hair-raising one-liners that instantly reveal their quirks, habits or dark secrets. There are aunties in dressing gowns and shower caps, and funny vignettes with unexpected props.

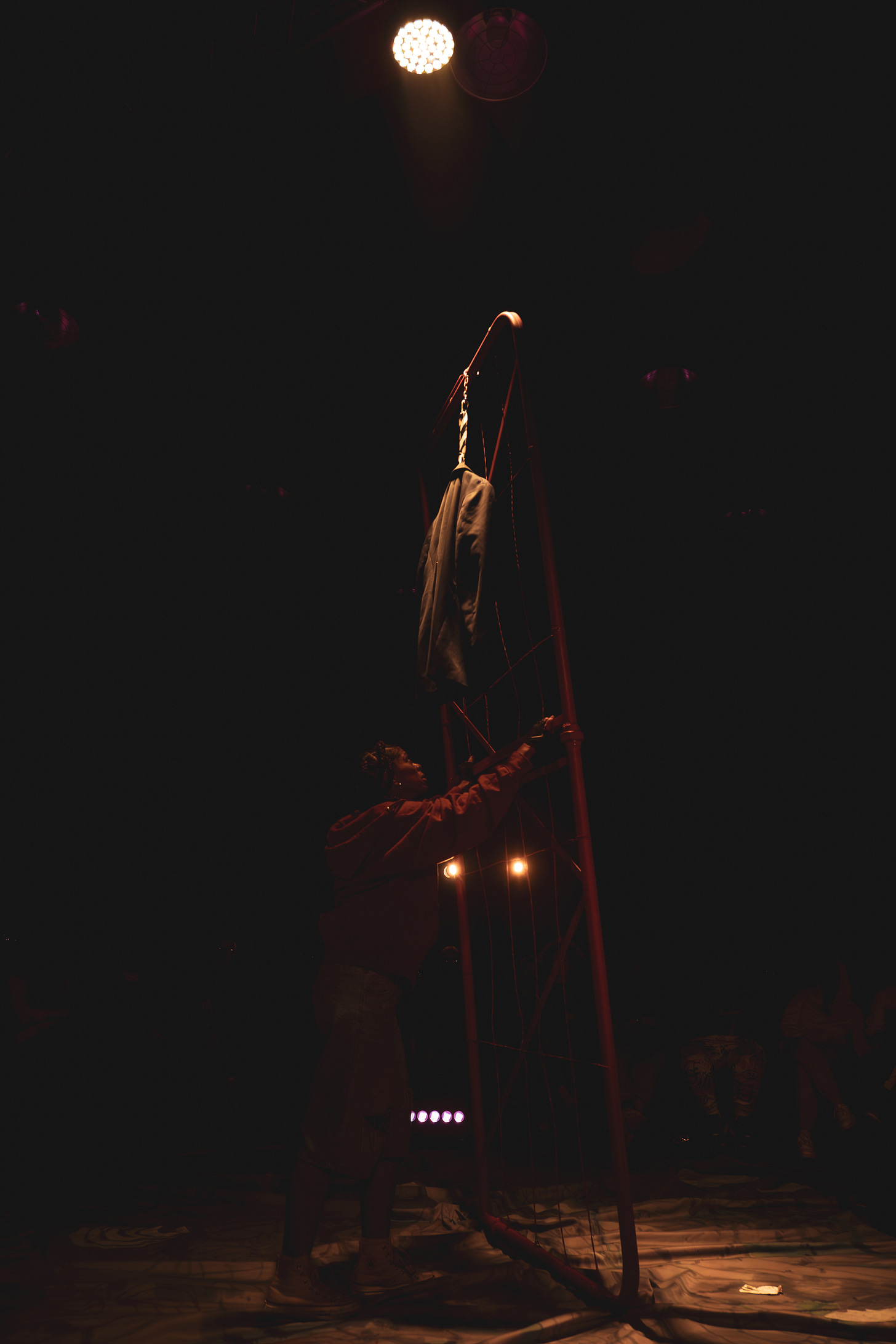

A central image is a funeral where the large metal farm gate that Nadia and Xavie carry onto stage at the start becomes a coffin borne by pallbearers chosen according to some complicated calculation of each family member’s relationship to the deceased.

Later, the gate is repositioned in a variety of ways to create other images, too, including its transition into a devastating evocation of child suicide.

Part of Van Rooi’s approach is to create imagery that can linger in the audience’s imagination. It’s this leaning into theatre’s power to make the audience in a sense a participant that made Kompoun among the stand-out shows at Suidoosterfees: it’s a play made for the stage, and its drama is as much in the words as it is in their delivery, and in the visceral experience of witnessing the two actors interact within the space, effectively reorganising the molecules in the room as they commune with the audience.

Jolyn Phillips, who wrote the stage adaptation of Kamfer’s novel, says that working on it made her think deeply about what it means to be a South African, about her roots, where she comes from, and about herself as something more than simply a representative of a particular race or class.

That resonated deeply with me. Even though Kompoun’s events and characters seem rooted in the specifics of an economically deprived farm community in the Overberg, the play dredged up overlaps with events I couldn’t resist remembering from my own upbringing in a privileged white community in apartheid-era KwaZulu-Natal. This flood of memories suggested something of the inherent humanness of experience even in disparate contexts; it was a reminder, too, that underneath all the layers of trauma and abuse and victimhood, there are real people doing what they must to survive.

In an interview, Kamfer has stated that her intension was to generate something beyond mere sadness with her novel; it’s the characters’ strength, their belief in a better version of the future and their rebelliousness that gives Kompoun its upbeat energy. Xavie and Nadia refuse to submit, refuse to give in, refuse to back down or be defeated by the past. As characters, they possess a kind of revolutionary zeal, are committed to the cause of personal liberation, of unshackling themselves psychologically, emotionally and physically from what has gone before.

There’s a line in the play that gave me goosebumps, prompted the tears to come welling up: “I can’t cry because part of me is glad for her.” It’s a reference to that aforementioned image of suicide, committed by a 12-year-old child so broken by abuse, so pushed to the edge, so unable to continue, that she had sought the only means of escape she had available to her.

That line echoed in my head long after the ovation at the end of the show had died down.

Despite the hard, sore realities it reveals, and the wounds it deals with by unrelentingly ripping the plaster off, Kompoun really does feels like an intervention. It feels like a light shone in the darkness, and it feels precisely like the kind of theatre we need to help lift curses inherited from the past. The clue is in another line that struck me hard: “Your father is buried and now we can breathe. Now you may live.” Amen to that.

* Kompoun will be performed at the National Arts Festival which takes place in Makhanda, South Africa, from 26 June to 6 July 2025.